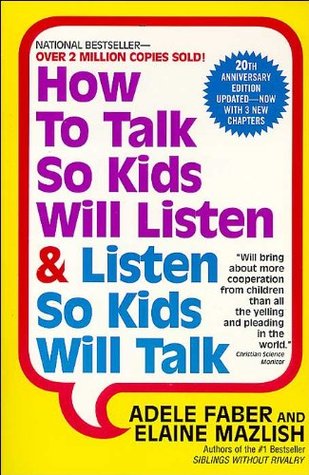

How To Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Can Talk is a parenting / communication book written by Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish. While this book is specifically intended for parents to have better relationships with their children, the vast majority of the advice contained within applies universally to all interactions, and I have written this summary specifically to abstract away from parent-child relationships. I consider the first chapter alone better at helping people internalize the principles behind nonviolent communication than Rosenberg’s entire book. HTTSKWL is currently by far my most highly recommended communications book, and because it is appealing to parents and children it is a remarkably easy read.

Note that unlike most books, this one contains a very high ratio of exercises and prompts and anecdotes relative to its advice. The authors recommend going through the book slowly, and doing all the exercises. This summary will only contain their explicit instructions – I highly recommend buying a copy of the book and completing it. The many specific example conversations will give a much better understanding of the principles I lay out here than I can convey in a summary.

General Perspective

Cultivating the attitude and mindset of compassion is far more important than any specific technique, advice, wording, etc.

We should always be communicating that the other person is capable and lovable, finding a way to feel good about ourselves and helping others to do the same, to live without blame and recrimination, to be sensitive to each other’s feelings, to be respectful of the needs of ourselves and others, to help people become more caring and responsible, and break the feedback loop of harmful interactions between ourselves.

Empathy doesn’t come naturally to us (and may even feel counterintuitive), so it is something we must learn and practice. It turns out that love, spontaneity, and good intentions are not always enough to ensure good results – we need real skills. Roleplaying and doing exercises can be incredibly helpful practice, particularly in advance of difficult real-world situations.

Sometimes people will tell us that empathy doesn’t work. Usually upon further investigation it becomes clear that they have fallen into a failure mode, of which there are many, including some very subtle. But if you are empathizing properly and it doesn’t seem to be working, it is probably still working. It takes time for people to update, especially when a pattern is very ingrained. It may take many attempts, and many successful repetitions, before the improvement becomes clear. Don’t resort to your old behaviors because it didn’t work the first time, there are many skills contained within to use, in combination and with increasing intensity. Some days are better than others, dramatic overnight results are rare, refuse to become discouraged!

It still may not be easy to empathize even if we know it works! It is easy to be accepting of someone’s emotions, right up until they say something that triggers us. That is okay too – you will always have another opportunity to express compassion. You may still act the same way as you did before, initially, but you have started to notice yourself doing it. That’s progress, the first step towards real change.

Remember that this book is not about giving you techniques to manipulate someone else’s behavior – it is about building cooperation and respect, in both directions. That requires you to be open and flexible, to truly hear and understand the other person, and taking that into account when interacting with them.

Dealing with feelings is more of an art than a science, and after a while you will develop a sense for what is helpful in each individual case. Life is not a clean little script that we can memorize and perform on command – but at least we can develop clear guiding principles that we can always return to.

The first chapter of this book teaches you to acknowledge feelings. That isn’t a prologue to the rest of the book, it is the main event, the foundation upon which everything builds. This one piece alone has the power to evaporate problems and change the entire nature of the relationship going forward, and this is something you always have the power to do unilaterally.

Chapter 1: Helping Children Deal with their Feelings

Fundamentally we want someone to listen to us and acknowledge our experience, this allows us to open up and talk about the problem, which in turn makes us better able to cope with our feelings and focus on solutions.

To help with feelings:

- Listen with full attention

- Acknowledge them with a word

- Give their feelings a name

- Give them their wishes in fantasy

Give them your full attention, do not pretend to be listening – put away other distractions and focus. Even simple confirmation you’re listening makes it easier for people to open up, nodding along or saying “okay” is sufficient.

By naming the other person’s feeling, you are demonstrating that you are modeling their internal experience. You must be specific, a generic “I know how you feel” does not convey that information. It is also okay to guess even if you are wrong, they will still recognize that you are genuinely trying to understand. People can also be feeling more than one thing at the same time. If the emotion is especially intense they may need to express it in other ways, e.g. physically, through an activity, etc.

Note that you can empathize with more than one person at once, for instance during conflict mediation. You will need to empathize with each one in turn, iterate between them, deescalate, and then it can turn towards problem solving or be resolved between them.

Do not follow up your empathy with a “but” – it negates everything that came before.

When giving them their desires in fantasy, go all-out with it. It is often helpful to write things down on a list.

Unhelpful ways people try to help:

- Denial of feelings

- Philosophizing

- Advice

- Questioning

- Defending the other side

- Pity

- Psychoanalyzing

When you begin to argue with someone’s feelings, you are effectively telling them not to trust their own perceptions. Don’t encourage people to push away feelings. Don’t try to explain the situation logically – they will be much more able to see the situation clearly if they feel understood. Resist the temptation to try to solve the problem immediately – even if it works you’re denying them the experience of wrestling with the problem and solving it themselves. Don’t ask them “why” questions, it feels like an interrogation and puts them on the defensive.

Note that you can accept someone’s feelings, even if you have to limit their actions (e.g. restraining someone from committing violence). You don’t have to agree with their position to acknowledge their experience either. People are more willing to accept limits if they are feeling understood.

Remember that empathy is not sympathy – you don’t have to take on their emotions in order to show them that you’re modeling their state.

Cautions

- People object when you repeat back things exactly

- Sometimes presence and comfort are desired, without words

- The response to an intense emotion must be sufficiently strong, and not stronger

- When they call themselves names, don’t use the word back to them (e.g. dumb, ugly, fat, etc.)

Chapter 2: Engaging Cooperation

Conflicting needs is one of the major sources of conflict.

To encourage cooperation:

- Describe your observations

- Give information

- Keep reminders short

- Talk about your feelings

- Write a note

The person may not see the current situation / behavior as problematic, begin by describing the situation in observational terms, avoiding any accusations or you-statements. This makes your position much easier to hear. Beware describing the situation passive-aggressively.

Give them relevant information about why the situation is problematic, there may be factors they haven’t taken into account, and will often come to the right solution for themselves. Allowing them to incorporate that information and make a decision is an act of confidence. Try to avoid giving them information they may already know.

If you need to give someone a reminder, keep it short and specific. A long explanation can come across as a lecture, or cause the person to lose interest.

When talking about your own feelings, be completely honest. Most people are not that fragile, and being polite is best reserved for small things, not when you’re already upset or need something urgently. If you hide what you’re feeling, it can build up and come out in worse ways later. Many people are relieved to hear that they can share their real feelings, as long as they’re giving information and owning their feelings as they do so.

You can leave people notes as reminders, or hand them notes directly. This opens up another route of communication.

Note that humor and playfulness is extremely powerful. The authors note that they originally held back emphasizing this in the first draft, because it is admittedly hard to be playful when you’re already upset yourself, but it is important enough to emphasize. Get in touch with the child-like side of yourself.

Attempts to coerce cooperation include:

- Blaming/accusing

- Name-calling

- Threats

- Commands

- Lecturing/moralizing

- Warnings

- Martyrdom

- Comparisons

- Sarcasm

- Prophesizing

Words can linger in people’s minds and become poisonous, they will remember them and use them against themselves later.

Questions to ask when you’re not getting through:

- Does the request make sense in terms of their ability?

- Do they feel like the request is unreasonable?

- Can we give them a choice about when / how to do something?

- Can the environment be adjusted to make cooperation easier?

- Is most of your time spend asking them to do something, is there enough time just spent being together?

You can ask them to repeat back to you to see if you’ve been heard.

If you’ve previously been very critical, you may need to use a lot of approval and overlook some behaviors. There will be a transition period, including hostility and suspicion on their part. Most people respond eventually.

Chapter 3: Alternatives to Punishment

The best alternative to punishment is prevention of the problem in the first place. This is something you can explicitly optimize ahead of time – come up with ideas before it becomes a recurring problem.

Ultimately punishment doesn’t work – when have you been punished in your life, and what effect did it have? It can lead to feelings of hatred, revenge, defiance, guilt, unworthiness, self-pity, and damages your relationship with them. It can also prevent them from internally confronting their own misbehavior – the punishment can be seen as “canceling” the original behavior, and thus effectively permitting it if they are willing to endure. They become focused on self-preservation, and away from problem-solving. Physical punishment also may encourage violent behavior in turn.

This requires a shift in attitude – and maybe a leap of faith that this will work. Stop seeing the other person as a problem in need of correction, or that they are trying to take advantage of us somehow, or that we always have the right answer. Neither of us is enemies, victims, bullies, competitors. Focus your energy on finding solutions that work for both sides and respect each person as individuals, give them tools and engage them in problem solving. We are helping others into a more productive mindset, helping them reflect on their mistake, think about how to fix it, and do better next time.

Alternatives to punishment:

- Point out a way to be helpful instead

- Express disapproval (without attacking their character)

- State your expectations / values

- Show them how to make amends

- Offer a choice

- Take action (remove, restrain, etc.)

- Allow the child to experience the consequences of their misbehavior

By giving people a way to make amends, it effectively gives them a ritualistic way to restore good feelings about themselves and their standing within the relationship. (Note that saying sorry is not sufficient – it is not an excuse to do the behavior again, remorse must accompany behavior change.)

Sometimes if you are giving the other person choices, it may feel like a forced choice, or a veiled threat. Allow them the chance to come up with their own choices instead (or sometimes offer an open-ended choice from the start). You may need to acknowledge their negative reactions and feelings before they will be receptive to any choices.

Punishment is a deliberate infliction or deprivation by another party, whereas consequences are the natural results of behavior, essentially reality itself providing feedback.

Problem solving steps:

- Talk about their feelings and needs

- Talk about your feelings and needs

- Brainstorm together to find a mutually agreeable solution

- Write down all ideas, without evaluating them

- Decide which suggestions you like, which you don’t like, and which you plan to follow through on

You cannot rush the process of talking about feelings, until the parties feel understood it cannot proceed effectively. Try to keep your own expression of feelings as short and clear as possible.

Let the other person come up with the first few ideas. Do not attempt to evaluate any ideas until everything has been written down – even unlikely ideas can lead to other creative solutions. When evaluating ideas, do not use put-down statements, instead talk about your reaction to them. Do not include consequences for failure as part of the problem-solving process.

Ensure follow-through by making a concrete plan. Focus on the future, not the past wrongdoings of either side. You may need to repeat things more than once.

If others are going through this process, avoid coming in and implementing a solution, let them work through it themselves.

Note that problems can be solved at any step along the way, you may not need to do the whole process every time.

Also note that an immediate solution is not always obvious. Going away from the problem and coming back to it can sometimes trigger the solution. At the very least, you will both be working from a place more sensitive of the other’s needs.

Life is about continual readjustment, no solutions are going to be permanent. Help the other party to see themselves as part of the process of generating solutions.

When a problem persists, it’s likely more complex than it appears. Give the other person the benefit of the doubt, and try to better understand what needs the behavior is serving.

Chapter 4: Encouraging Autonomy

When in a dependent position, people might feel some gratitude, but often feel helpless, worthless, resentful, frustrated, and/or angry. Allow people to do things for themselves, wrestle with their own problems, and learn from their own mistakes. The skills explained to date all help others see themselves as separate, responsible, competent people. Opportunities to encourage autonomy present themselves every day – every small choice gives them a chance to exert control over their own lives.

To encourage autonomy:

- Let others make choices

- Show respect for their struggle

- Don’t ask too many prying questions

- Don’t rush to answer questions

- Encourage people to use external sources

- Don’t take away hope by protecting them from disappointment

It is always hard to do something new. Telling people that something is easy is setting them up for feeling bad about failure. If you are giving them advice on how to solve the problem, try to hedge your advice in case it doesn’t work (e.g. “sometimes it helps if…”)

Listening with curiosity will help people open up naturally, without questioning. The urge to question, and to fix others’ problems, is strong, and usually unproductive. You can always tell someone you are open to talking, or observing that they look upset, and letting them choose to open up or not.

We are tempted to reflexively answer questions. Instead, see yourself as a sounding board for exploring thoughts, you can always answer a question directly later on. Searching for an answer is a valuable process in and of itself, don’t deprive them of the mental experience.

We are all embedded in a larger world, there are valuable resources waiting to be tapped, show them what is available for their use.

Protecting people from disappointment will also protect them from striving, having dreams, hoping. Much of life’s pleasure involves anticipation. Even just talking about dreams can be enough to feel satisfied.

Note that it may be difficult to encourage autonomy from ourselves. When we are busy and impatient, it can be convenient to do things for others because it is quicker. Dependence can also generate strong feelings of connectedness, and it feels satisfying to be needed. This can take restraint and discipline to hold back.

More ways to encourage autonomy:

- Respect their physical boundaries

- Stay out of the minute details

- Don’t talk about them in the third person in front of them

- Let them answer their own questions

- Show respect for their eventual readiness

- Watch out for saying “no” too often

Alternatives to “no”:

- Give information

- Accept their feelings

- Describe the problem

- Substitute a yes for a no (e.g. yes, later)

- Give yourself time to think

Instead of advice:

- Help sort out tangled thoughts/feelings

- Restate the problem as a question (and don’t answer immediately)

- Point out external resources

Even if they don’t come up with their own answer, they’re more likely to give our ideas a fair hearing after feeling heard. Preface suggestions with “how would you feel if…” / “would you consider…” to acknowledge that your solution might be seen differently by them.

This doesn’t mean you can literally never do things for other people – listen to your sense of whether they are in need.

Chapter 5: Praise

Our sense of self-worth has a profound effect on all aspects of our lives. By default, the world is quick to criticize and slow to praise. We each individually have a responsibility to reverse this pattern, to affirm the fundamental sense of rightness in others. What we say to others will get internalized and stored, these words can become important lifelong touchstones. When people feel appreciated, they will feel good about themselves, set higher goals, and cope with challenge more effectively.

Praise is tricky to get right – the temptation is to fall into simple one-word evaluations like calling people “smart” or “good”. This can provoke doubt or denial and focus them on negatives, provoke anxiety, it might feel threatening or comfortable, or it might come across as manipulative. Beware of praise by comparison as well.

Helpful praise involves describing what they did, and what you like about it. This appreciation opens the door for them to praise and appreciate themselves, and recognize their own strengths and virtues. This style of praise is definitely more of an effort than giving one-word evaluations, it involves seriously observing the outcome, noticing your own feelings about it, and stating this out loud. Even if you slip into evaluative statements accidentally, you can always elaborate further in the above manner to catch yourself.

Cautions:

- Make sure the level of praise is appropriate to their ability (don’t praise something trivial)

- Avoid hinting at past weaknesses or failures

- Excessive enthusiasm can feel like pressure, interfere with internal motivation

- Be prepared for a lot of repetition of the praised activity

If the person is still fearful of risking failure:

- Don’t minimize their distress, understand the feelings

- Accept their mistakes and view them as part of learning process

- Accept our own mistakes, to model this process for them.

Chapter 6: Freeing Children from Playing Roles + Chapter 7: Putting it All Together

Self-fulfilling prophecies are very real, and dangerous, and it can often start innocently (e.g. trying to explain someone’s behavior to others). Labeling people should be avoided at all costs – and this can be conveyed non-verbally as well, with looks or tone of voice. Especially when you spend a lot of time with one person it can add up to a profound amount of reinforcement of these patterns.

To free people from playing roles:

- Look for opportunities to show them a new picture of themselves

- Put them in situations where they can see themselves differently

- Let them overhear you say something positive about them

- Model the behavior you’d like to see

- Remind them of their good moments that contradict their self-impression

- When they behave according to the old label, state your feelings and/or expectations

Freeing someone from playing out roles is complicated, it involves an entire change of attitude, and all of the previous skills. With persistent behavior, it takes an act of will not to reinforce the pattern, we have to deliberately plan ahead and practice.

We need to avoid casting ourselves in roles either – we are human beings with a great capacity for growth and change. Be as kind to ourselves as we would be to others.